Paul

Stone

Shameful Carry On

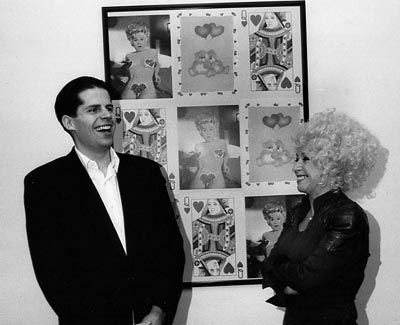

The author (left) with Barbara Windsor (right).

Background: Paul Stone, ‘Saucy’, 1990.

Photo: Rik Walton.

When asked to write about Carry On films for this publication, it was not without some trepidation that I accepted. Firstly, I have to declare that I am a fan and fandom often implies a degree of unquestioning loyalty, of solitary pleasure in the chosen subject of your affections. I don’t know that I want to spoil my special relationship with these films. Further, greater minds than mine have attempted an analysis of the Carry Ons. Hell, they were even honoured with there own Barbican retrospective a few years back. Sifting through my collection of books and newspaper clippings on the subject – collecting being such an important element of fandom – has only reinforced my feelings of how sometimes I’d sooner keep my own company of personal thoughts about these films. A bit like masturbation, I’m not sure the pleasure derived warrants huge examination but, as Ross Sinclair once wrote on the subject (in the catalogue to 1994’s ‘New Art in Scotland’ at the CCA): "...why does masturbating always get such a bad press? I’m a big fan myself". I don’t know that I have anything to add – but here goes anyway – though, for some reason, the vision I currently have in my mind is that of the illusive Oozalum bird in Carry On Up the Jungle, who made itself extinct through its unique talent to disappear up its own behind.

Whilst writing this I was reminded of ‘The case of Peter’ in

RD Laing’s seminal sixties book ‘The Divided Self – An

Existential Study in Sanity and Madness’. To cut a long story short,

by the time he had come to be patient of Dr Laing, Peter had gone from

model pupil and office worker to an unemployed wreck crippled by guilt

and anxiety, unable to engage with the outside world. A compulsive masturbator,

he saw himself and the objects of his fantasies as hypocrites, with all

outside appearances of ‘normality’ and ‘decency’ a

facade masking feelings of worthlessness and the desire to do harm to

others. Unable to form intimate relationships with others, he became convinced

that he emitted a rancid odour from his lower body despite bathing several

times a day and that others could see his inner, darkest thoughts manifested

in his face.

Maybe, I was reminded of this story because my Carry On actor of choice

is Kenneth Williams. More than any other he represents the undercurrent

of sexual repression and thwarted desires that runs through the series,

blighted by his own inability to reconcile his personal ambition with

the reality of his life. Well read and with many ‘serious’ acting

achievements under his belt, he openly disparaged the Carry On films,

thinking them beneath him (but he needed the money). Feeling himself typecast,

he resented the critical acclaim and careers of his acting contemporaries.

Despite holidaying in the flesh-pots of Tangier with the likes of Joe

Orton, he was ever fearful of both his own sexuality or any physical intimacy,

his painful loneliness exacerbated by a litany of bodily ailments. Published

after his death, his diaries make for a bleak and bitter read, full of

his constant need to berate others’ for sins he was only too guilty

of himself. The diaries represent a chronicle of a life blighted by disappointment,

where the notion of choice was more often than not viewed as presenting

the unwelcome possibility of failure.

With their roots firmly in the traditions of music hall revues and saucy

seaside postcards, the Carry Ons are undoubtably vulgar, full of references

to bodily functions and base desires, cross-dressing and a delight in

seeing pomposity of authority deflated. Only after the series finished

after twenty years in the late seventies (please, can we forget the act

of necrophilia that was the nineties’ Carry On Columbus) were they

truly accorded critical recognition. Yet, is their very vulgarity that

always attracted me to the films. Their ‘failure’ to achieve

‘sophistication’ is what makes them so appealing, especially

today where success and ‘good’ taste are commodities and less

than physical perfection is something to be ashamed of.

Having been born in the mid-sixties, I’m too young to have any first-hand

recollection of the first half of the period of the Carry Ons’ production,

but old enough to remember the Britain of the seventies that informed

the latter half of the series. Besides, my personal knowledge is based

on viewing the films on TV, in a non-chronological order. Not that chronology

or history is particularly vital to an appreciation of these films. The

series can be broadly be divided into two camps – the ‘historical’

costume drama ones (such as Cleo, Henry and – oh yes – Dick)

and those rooted firmly in contemporary, more mundane life (insert profession

of your choice, preferably medical). The one exception to this –

unless you believe in resurrecting the dead – and my personal favourite

is Carry On Screaming. References to current events may lose their impact

with the passing of time, but this is counterbalanced by the wider understanding

today of some of other references – especially those to matters sexual

– the films contain.

I might have varying levels of recollection of the seventies, of the oil

crises and three-day weeks that inform the humour of many of the series,

but it would be disingenuous to pretend that I possessed any political

perspective at such a young age. At the time, power cuts represented an

opportunity to skip school and buy a torch rather than to contemplate

shifting definitions of class, global economics or the government’s

battles with the unions. Additionally, I would wish to avoid appearing

to be a participant in some perverse nostalgia trip. Indeed, to me, nostalgia

is a dirty word. Being a True Fan, I partially resent the Carry On’s

rehabilitation by various modern commentators. By this I mean the ironists

and kitsch-mongers, usually people around my own age, who think their

Spangles-and-space-hoppers retro regurgitation of their childhood is in

any way interesting rather than merely a smokescreen for the guilt they

feel in deriving unadulterated pleasure from simple things (and a way

of keeping Gail Porter off the dole). A notable exception to the latter

– because he was also a True Fan and was another ‘companion’

to my teenage years – is Morrissey, someone whose own career was

founded on a nice line in guilt, repressed desire and general miserablism

and whose appeal is only enhanced by the fact that it all went a bit off

the rails towards the end.

The Carry Ons largely owe their continued popularity to repeated showings

on the small screen. But it was growth of television, especially the availability

of colour television, that was instrumental in killing off much of our

domestic film production. Though the belief that we ever lived in more

‘innocent’ times is questionable, the more literal – if

not necessarily liberal – depiction of sex on the TV and Hollywood-dominated

cinema screen today, is something alien to the essentially chaste world

that the Carry On films inhabit. The series attempts to remain relevant

in its dying days were woeful and 1978’s final entry – the faux

soft-porn Carry On Emanuel – represents a limp climax.

More telling perhaps is the finale of 1969’s Camping, where the frustrated

(in every way) campsite inhabitants turn on the ‘hippy’ gathering

in the adjacent field. This reflects the feeling that, though the social

revolution of the sixties undoubtably had some positive effects in terms

of unseating ‘the establishment’ and opening up access to opportunities

for the working class (who constituted the majority audience for the Carry

Ons), the accompanying sexual revolution was not necessarily as welcome,

still cited today as a the root of various of society’s ills. However,

this is not to say I think the Carry Ons present a reactionary view of

life. Superficially, they could be read as championing safety in conforming

to the status quo. I favour a more affirmative reading of them as an acknowledgement

that no ideology or individual is beyond criticism (or ridicule) and that

it is the quirks and petty prejudices of human nature – whether concealed

or not – that ultimately guide our lives.

Notions of individuality and self-reliance or determination were given

a bad name by their hijacking in the conservative eighties, an attitude

we all supposedly abandoned in the touchy-feely world we live in today

(whilst secretly suspecting everyone else but us is on the make). On the

other hand, through over-contemplation, I may have fallen into the very

trap I hoped to avoid, becoming paranoid and overly suspicious of others’

motivations in the process. Maybe life (and life as reflected in the Carry

Ons) is just about trying to ride out disappointments, of grasping moments

of pleasure when they arise and trying to make a decent fist of things.

Which kind of brings me back to the subject of masturbation and where

I came in. Kenneth Williams – on receiving an offer of work after

a particularly dry spell – wrote in his diary: "Quite the barclays

[as in Barclays Bank] tonight before bed. Masturbatory success is the

result of imaginative conceit". Sometimes, the solitary pleasures

are the best.

Paul Stone lives in Newcastle upon Tyne. He is an artist, co-director

of artists’ agency Vane and International Coordinator for [a-n] MAGAZINE.